In the first part of this blog we already already into what neurodata are and whether they protectedand by the GDPR.

In this part of, we will examine whether the GDPR provides adequate protection and the potential consequences that may result from the inadequate protection of neurodata.

1. Does the GDPR provide sufficient protection?

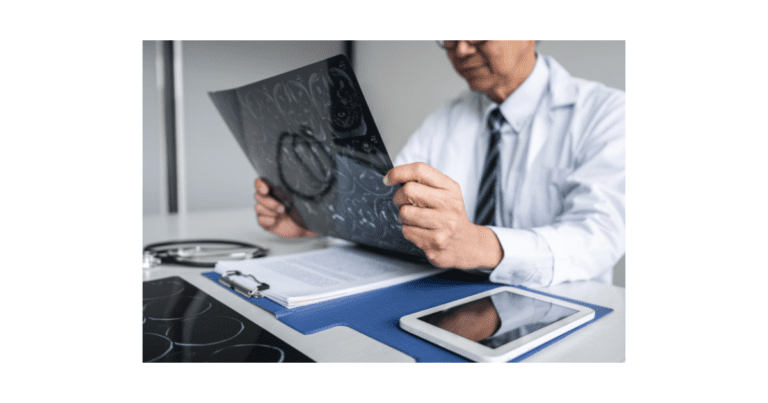

As discussed in the first part, there exists equipment that can make brain recordings and whose data can potentially be used by third parties.

These data and their potential reuse by third parties can raise serious ethical and data protection concerns.

Indeed, there is a range of devices for non-medical applications under development, for a variety of applications such as e.g., gaming.

These devices are currently marketed by companies such as Emotiv and Neurosky.

Fortunately, these are not yet as common as cell phones, laptops, and so on. This may be due to the absence of apps, or problems with ease of use, or perhaps a lack of perceived need.

However, it is no secret that more and more technology companies are announcing their entry into the field and investing significant amounts of money. These developments highlight the intent to develop brain interfaces for consumers and essentially link computers directly to our brains.

Elon Musk is one of figures investing huge sums of money in such developments. There is also Kernel, a multi-million-dollar company based in Los Angeles, wants to “hack the human brain.

More recently Facebook has joined them, they too want to discover a way to control devices directly with data derived from the brain.

A commercial enterprise with sufficient data and signal processing capacity could be well placed to derive potentially sensitive information from a body of recorded brain activity, which is itself quite meaningless.

This may be exacerbated using adaptive learning algorithms that work with large amounts of data.

A wide variety of user information can be derived without requiring users to do anything special. All it takes is for them to use their computer through the BCI.

The fact that one can infer certain very intimate thoughts and the mental state of an individual from this brain data, and that this data is likely to be increasingly commercialized in the future, is significant in terms of Article 9.1 of the GDPR.

How data is or is not classified as sensitive affects the level of protection required by the regulation.

In the GDPR, this classification is based on the purpose of the processing. If neurodata are obtained through medical devices, for example BCI in motor or speech rehabilitation, these data will qualify as health data.

One might ask whether neurodata still qualifies as health data if it comes from consumer neurotechnology offered by companies such as Facebook, Kernel and Neuralink.

This does not seem to us to be the case since these data were not recorded for health-related reasons.

With respect to health or medical data, Article 9 of the GDPR prohibits processing unless exceptions are met. n summary, if data of a special category is to be processed, in addition to a legal basis under Article 6 of the GDPR, there must be a legal basis under Article 9 of the GDPR.

Does this mean that if the brain data comes from companies such as Facebook, they do not enjoy the protection of Article 9? The GDPR does not give a clear answer to this.

Specifically, we can infer the following issues:

- Brain data is a special case of data in that its meaning may vary depending on its processing, regardless of the purpose of its capture.

- The categorization of brain-derived data is unclear in terms of the GDPR if it is neither health nor medical devices.

- Data protection legislation should distinguish between different data types and the degree of data sensitivity of each type. Specifically, it should look at how likely the data is to reveal sensitive personal data. Specifically, the probability of the data revealing sensitive personal data should be considered.

To date, the GDPR does not provide a solution to the above problems. This is problematic, after all, neurodata is becoming more relevant by the day.

Beyond the GDPR, however, there are other concerns about BCI-related data. Providing appropriate protection to data subjects through regulation may not be enough.

As is common knowledge from the way smartphones are used, especially in terms of commonly used apps and social media, data subjects readily consent to their data being recorded and used, if they get something useful in return.

After all, in terms of social media, we “pay” with our data for the goods and services of the platform in question. Very likely, this will also become the business model for neurodata.

And for this, the current GDPR – and policies in general – do not suffice.

2. What are the potential risks if neurodata is not adequately protected?

If the GDPR and other privacy regulations are not worden adapted that they offer concrete solutionsand to the problem of neurodata, we can expect the following problems:

- Outside companies could buy neurodata from BCI companies and use it to make certain essential decisions, such as whether someone gets a loan or access to health care.

- Courts could order neuromonitoring of individuals who may commit crimes, based on their history or socio-demographic environment.

- BCIs specializing in “neuroenhancement” could become a condition of employment, as in the military, for example. This would blur the lines between human reasoning and algorithmic influence. As with all industries where data protection is critical, there is a real risk of neurodata hacking, where cybercriminals gain access to and exploit brain data.

As with all industries where dataprotection is critical, there is a real risk of neurodata hacking..

In doing so, it would cybercriminals access can get to the neurodata of a huge number of persons and this data can operate for their own personal goals.

3. Conclusion

Neurodata is increasingly becoming an important factor in our lives.

It can do very good things for society, think of the paralyzed man who could tweet back in 2021 because of BCI technology. But like many wonderful things in life, neurodata can become dangerous if we don’t provide the necessary measures.

We may reach a point in the future where our thoughts can be used and sold by companies like Facebook. It is therefore essential that GDPR and other data protection legislation focus more on neurodata and actively look for ways we can protect it.